Divine labours, devalued work:

Sneha Banerjee &Prabha Kotiswaran Published online: 08 Nov 2020

ABSTRACT

This article offers a feminist critique of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019. Fifteen years since the first proposed regulation of assisted reproductive technologies and surrogacy, the 2019 Bill leaves much to be desired. It reflects a limited understanding of the complexities of surrogacy, is discriminatory in its approach, is plagued by lack of clarity, is unrealistic and most importantly, does not include adequate safeguards for the surrogate. Women’s reproductive labour in performing surrogacy is valorized but not compensated. Even though the Bill may well accept some recommendations of the Rajya Sabha select Committee, its failure to address issues that we highlight will mean that if passed, it will be challenged in the courts on constitutional grounds. This will generate uncertainty for years, for many infertile couples and individuals who look to the law for streamlined regulation, defeating its main purpose in facilitating a novel mode of reproduction.

Introduction

Surrogacy is a novel and arguably desirable opportunity for family formation for many individuals and couples, while simultaneously being a maelstrom for a range of ethical issues implicating numerous legal fields. In the past decade or so, these complexities have become exacerbated through reproductive tourism enabled by globalization. Governments have globally engaged in a form of “regulatory arbitrage”, whereby the prohibition of surrogacy (commercial or altruistic) in certain countries leads to more permissive legal regimes elsewhere. For feminists in particular, surrogacy presents a formidable challenge. On the one hand, it queers compulsory heteronormativity and the heteropatriarchal family-form while on the other, generating exploitative arrangements for surrogates in the global South as reproductive markets present favourable economic terms and bargaining power for intending parents from the global North. Correspondingly, the law has become a site for intense political, social and economic contestation over the status of women’s reproductive labour. 1 In this article, we offer one feminist perspective on the regulation of surrogacy by focusing on a critique of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2019 (hereinafter the Bill) which was passed by the Lok Sabha in August 2019 and which is due to be presented before the Rajya Sabha in the next session of Parliament. We start by offering our assessment of the feminist normative landscape on surrogacy and then chronicle India’s efforts to regulate surrogacy. We then undertake a detailed analysis of the Bill along four axes, namely, locating surrogacy in the larger milieu of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) and examining eligibility criteria for commissioning surrogacy, the issue of “compensation” for surrogates and finally, the criminalization of surrogacy in the Bill, while paying particular attention to whether the Bill in its current form will pass constitutional muster. We conclude by reflecting on what India can learn from international trends on surrogacy law and policy. Needless to say, the social realities of surrogacy invite consideration of numerous other legal issues which are beyond the scope of this article. However, we hope that our snapshot view of the Bill as it stands today will help inform debates as the Bill enters the final stages of deliberations by Parliament, making possible the culmination of a regulatory journey that began nearly fifteen years ago.

Feminist theorizing on surrogacy

Surrogacy has long been a fraught domain for feminists. Alison Bailey notes that Western feminists theorized surrogacy in two phases: an intensely normative phase in the 1980s when they offered liberal, Marxist and radical feminist analyses of commercial surrogacy and since the mid-1990s, through a discernible biomedical ethnographic turn to understand how surrogacy work is lived, embodied and negotiated, thereby heralding a move from moral certainty to moral ambivalence. 2 Indian feminists similarly offer both normative and ethnographic theorizing on surrogacy, even if there is no temporal distinction between these enterprises. Liberal feminists support commercial surrogacy with adequate safeguards 3 while radical feminists view reproductive tourism as being at the crossroads of reproductive, sexual and labour trafficking 4 with commercial surrogacy being an exploitative trade in reproductive body parts. 5 Marxist feminists similarly view commercial surrogacy as a form of reproductive trafficking. 6 Kumkum Sangari maps how commercial surrogacy amounts to the appropriation of women’s reproductive labour by ‘biocapital’ 7 and is organized in the form of a post-Fordist manufacturing model characterized by flexibility where the burden of uncertainty and repeat failure is on the women 8 whose voices are lost through the triple discourse of “remediable poverty, calibrated entrepreneurialism and familial altruism”. 9

Most Indian feminists adopt a materialist feminist position wherein surrogates are understood as subject to the twin forces of capitalism and patriarchy. Amongst these are several feminist ethnographers who view surrogates as performing highly gendered, exceptionally corporeal, and stigmatized 10 reproductive labour 11 against the backdrop of structural inequalities, an aggressively anti-natalist state, a larger project of neo-eugenics 12 and “stratified reproduction” wherein a race-based reproductive hierarchy is sustained by the international division of labour and intentional state policies. These feminists are pragmatic towards regulation and oppose bans on commercial surrogacy, informed by a view that the market will be driven underground if surrogacy is banned, in turn harming surrogates.

Our own position mirrors this materialist feminist approach. In the context of gestational surrogacy (where the surrogate cannot use her oocytes) provisioned through a highly medicalized ART industry, the work of surrogates is technologically-aided, affective reproductive labour. We recognize that women undertake surrogacy under highly unequal conditions of capitalist patriarchy, but do not find it exceptional in relation to a range of other forms of gendered reproductive labour, including domestic work, erotic dancing, sex work or unpaid care and domestic work done by housewives, such that it warrants exceptional treatment by the state. We acknowledge power differentials, constrained choices and exploitative relations shaped by a globalized context and believe that women’s agency in wanting to become surrogates for a fee cannot be dismissed as false consciousness. Finally, we are opposed to prohibitionism and blanket bans, which are oblivious to the lived realities of surrogates and instead focus on how law can ensure economic justice for them.

Regulatory landscape of surrogacy in India

India is probably one of the few countries in the world to have adopted every possible regulatory approach to surrogacy in the space of fifteen years. An early attempt was made by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in 2005 through the National Guidelines for Accreditation, Supervision & Regulation of Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinics in India. Thereafter, separate chapters on surrogacy were included in the various versions of the Draft Assisted Reproductive Technologies (Regulation) Bill (hereinafter the ART Bill) proposed between 2008 and 2013. These laws were liberal in their regulatory approach towards ARTs and surrogacy. Between 2012 and 2016, however, the proposed laws became increasingly restrictive. The proposals went from being highly favourable to fertility clinics (and less so to surrogates) to severely restricting actors who could avail of ART on the basis of marital status, sexual orientation and nationality/citizenship with correspondingly increasing levels of protection to surrogates. Between 2012 and 2015, administrative orders issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs regulated the visa requirements for foreign intending couples who sought surrogacy services in India, introducing a new visa category before moving towards a prohibition 13 for such couples in 2015 in response to a public interest litigation 14 filed to prohibit commercial surrogacy.

In 2016, the government decided to address the regulation of ARTs and surrogacy through separate legislations and introduced the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016 in the Lok Sabha on 21 November 2016. A draft Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill, 2020 was introduced in Parliament on 14 September 2020 (2020 ART Bill). 15 The 2016 Bill which sought to prohibit commercial surrogacy and permit only altruistic surrogacy under limited conditions was meanwhile referred to a Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee (PSC) on Health and Family Welfare which submitted the 102nd report in August 2017. Based on extensive consultations with numerous stakeholders (governmental and otherwise), the Committee recommended the reversal of almost every key feature of the 2016 Bill. It proposed a “compensated” model for surrogacy over an altruistic form and stated that surrogates did not have to be close relatives of the intending parents. It also liberalized the eligibility criteria for intending parents by extending the surrogacy option to live-in couples, divorced women, widows, non-resident Indians (“NRIs”), Persons of Indian Origin (“PIOs”) and Overseas Citizens of India (“OCIs”) and required only one year of proven infertility before availing of surrogacy. However, the 2016 Bill lapsed with the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha in 2019. The 2019 version of the Bill was re-introduced in the Lok Sabha on 15 July 2019 and was passed on 5 August 2019 (Bill No. 156-C of 2019) without incorporating any recommendations of the PSC report. It was then introduced and debated in the Rajya Sabha on 19 and 20 November 2019.

During the debates in the Rajya Sabha on the Bill, numerous MPs spoke eloquently on many of the key issues that the Bill fails to address. To highlight a few examples: who can be an intending parent, particularly referring to marital status and citizenship, 16 how infertility is defined, 17 the stigma around infertility in a patriarchal context 18 and the possibilities of harnessing scientific advancement to address such concerns, 19 the lack of focus on the rights of children born out of surrogacy, 20 the question of compensation to the surrogate and disregard of the recommendations of the PSC Report in this Bill. 21 As Rajya Sabha MPs repeatedly pointed out, consideration of this Bill was woefully incomplete in the absence of the ART Bill. In light of these reservations expressed by several MPs, the Bill was referred to a Select Committee of the Rajya Sabha (RSC) that examined it, undertook field visits around the country and submitted its report on 5 February 2020.

The RSC underscored the importance of passing the ART Bill before the Surrogacy Bill since the medical processes involved in the latter are best regulated through the ART Bill. This report reiterated several recommendations made by the PSC. It emphasized the need to broaden eligibility criteria for who can be a part of surrogacy – permitting PIOs and OCIs, widowed and divorced women to commission a surrogacy and any “willing woman” within the prescribed age limit and meeting other criteria to act as a surrogate without having to be a “close relative.” The RSC noted that surrogacy can be medically indicated rather than having the intending couple prove infertility over an extended period of unprotected coitus. This report however, upheld the Bill’s approach of allowing only altruistic surrogacy thus rejecting both commercial and compensatory surrogacy. It noted that, “both … commercial and compensatory surrogacy is (sic.) fraught with the risk of exploitation and commodifying the noble instinct of motherhood” 22 and in a rhetorical move, asked “whether such a sublime and divine instinct of motherhood could be allowed to be turned into a mechanical paid service of procreation devoid of divine warmth and affection.” 23 However, it did allow for an expansion of the insurance cover that the surrogate could receive to include medical costs (rather than only cover loss, damage, illness or death as listed in the Bill) and other “prescribed expenses” for a longer duration of 36 months in contrast to the 16 months’ duration envisaged by the Bill. The RSC unlike the PSC did not detail what would comprise “prescribed expenses.”

A feminist critique of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019

Against this backdrop, we offer a critique of the Bill in order to ensure non-discrimination, equality of access to surrogacy and economic justice for surrogates. A broader engagement with the normative questions around law and reproductive technologies is beyond the scope of this article. As the Indian state inches closer towards prohibiting commercial surrogacy, our critique highlights key areas that can, and must be rethought and reworked before being presented to Parliament for reconsideration, especially in view of the two parliamentary committees’ reports. In particular, we interrogate the following aspects: the relationship between surrogacy and ARTs, eligibility criteria for intending parents and surrogates laid down in the Bill, the issue of “compensation” for surrogacy, and the implementation and enforcement provisions of the Bill.

Surrogacy and ARTs

The Bill and the ART Bill are complementary legislations in various ways. Seeking to pass the Bill in the absence of the ART Bill produced confusion as illustrated below – in terms of definitions of key medical procedures and overlaps in their regulation, the absence of regulation of gamete donation, and protection of the rights of children born out of surrogacy. Despite introduction of the 2020 ART Bill, all these issues remain inadequately addressed.

The use of ARTs is central since only gestational surrogacy is permissible under section 4(iii)(b)(I). However, it is a glaring gap that the Bill does not include a definition of the very important term – “Assisted Reproductive Technology.” Section 2(zc) which defines “Surrogacy”, does not mention use of ARTs whereas the definition of “surrogacy procedures” [section 2 (ze)] and “surrogate mother” [section 2 (zf)] include it, demonstrating inconsistency. Similarly, the definition of “commercial surrogacy” in section 2(f) refers to In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), an ART procedure. The definition of “commercial surrogacy” in section 2(f) for instance refers to IVF, an ART procedure, only by implication through the phrase “component procedures”, and not directly. 24 In the absence of the ART Bill, it was unclear as to how the “component procedures” of surrogacy are to be regulated. It would be ideal for the definition of surrogacy to only mention “services of surrogate motherhood” to avoid conflating surrogacy with a vast array of ARTs. Finally, the registration requirements set out in Section 10 for surrogacy clinics need to be aligned with corresponding provisions of the ART Bill especially since all fertility clinics regulated by the ART Bill may not conduct surrogacy but all clinics that conduct surrogacy will be fertility clinics that offer IVF services. In light of such drawbacks in regulating surrogacy in the absence of an ART Bill, the RSC rightly recommended that the ART Bill be introduced prior to this Bill.

Meanwhile, the 2020 ART Bill, as introduced in the Lok Sabha makes it mandatory for all establishments offering ARTs to be registered and lays down informed consent procedures. 25 It provides that the national and state boards under the 2020 ART Bill will be the same as the Surrogacy Boards created under the Bill. The two Bills however create multiple agencies for purposes of registering surrogacy clinics and ART clinics and banks. Thus, the processes needed for implementing the two legislations do not seem to be streamlined. 26

With regard to the eligibility certificate to be obtained by the surrogate, Section 4(iii)(b)(I) 27 specifies that no woman (other than an ever-married woman with a child and between the ages of 25 and 35 years) can be a surrogate mother or donate her egg or oocyte. This provision is poorly drafted. On the face of it, it appears as though a surrogate mother could potentially donate her eggs. However, from subclause (III) 28 we can conclude that the surrogate mother cannot donate her gametes. Similarly, in Section 39 (dealing with a presumption of coercion in case of surrogacy) there is reference to the woman who donates gametes for surrogacy. Since egg donation is highly likely in cases of surrogacy which are medically indicated, it is necessary to have protocols and regulations for the same. If the Bill visualizes the donation of gametes (specifically eggs) and eligibility criteria for such donors, then it must streamline the gamete donation process in this Bill and specify in detail provisions for protection of the egg donor as well, on par with the surrogate, which are currently missing. Otherwise, it appears that the egg donor cannot even expect that her medical expenses and the costs of insurance coverage will be met by the intending couple. Egg donation is more appropriately a subject matter for the ART Bill yet the 2020 ART Bill also does not provide adequate protection for the egg donor allowing only for insurance coverage for medical complications or death.

Similarly, section 35(1)(e) prohibits a person or organization from selling a human embryo or gamete for the purposes of surrogacy. The rest of the subclause deals with organized networks that actively buy and sell embryos and gametes in relation to which the prohibition is reasonable. However, it is unclear under what conditions the intending couple can secure either sperm or eggs in order to complete the surrogacy. The term “sell” needs clarification here. If gamete donation is envisaged, then the conditions under which this is permissible must be specified, which may well be regulated by the ART Bill. The 2020 ART Bill specifies no protocols in this regard. Further, the subclause needs qualification in a manner similar to the proviso to section 3(vii) which prohibits the storage of an embryo or gametes unless it is legally stored by sperm banks and IVF clinics or for purposes of conducting medical research. There needs to be a clarification regarding the transactions that would involve retrieval from storage for use, what entails “use”, who can do so and under what conditions, including the question of “sale”, costs involved or compensation as may be relevant.

Section 4(iii)(b)(IV) says that a woman can be a surrogate only once, however, there is a need for standardization of the number of embryos that can be transferred in any given attempt of an IVF cycle with the ART Bill. This Bill stipulates that the number of attempts that the surrogate mother can be subjected to will be “as prescribed”, but instead of rules under this Bill, it is more appropriate to regulate such medical protocols through the ART Bill. Moreover, Section 3 (vi) mentions compliance with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971, but is silent on the phenomenon of “foetal reduction” where multiple pregnancies are reduced to a singleton or twins, a practice that is fairly common in pregnancies induced by IVF, including gestational surrogacy.

Last but not the least, in a techno-intensive mode of reproduction it is imperative that there are safeguards for the children born of surrogacy. However, it has not been adequately included in this Bill. The Bill is silent on whether there should be any genetic link between the intending couple and the child. Many jurisdictions 29 around the world that permit surrogacy insist on such a link, with at least one of the intending parents. 30 In fact, the Law Commission of India in its 2009 report on the subject required this in its recommendations (para 4.2[1]). 31 There is a need to include provisions for the child to have a right to know the identity of the surrogate mother or the individual donating gametes (if relevant) in the surrogacy procedure. A child’s right to know is an established human rights principle in the context of adoption, and increasingly relevant with the expanded use of reproductive technologies. It is in consonance with the spirit of “best interests of the child” and derived from Articles 7 and 8 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. 32

Further, the Bill needs to deal more comprehensively with scenarios where a child born from surrogacy is not accepted by the intending parents. Section 2(a) defines an abandoned child as one that is born out of surrogacy, has been deserted by the intending parents or guardians and has been declared as abandoned by the appropriate authority. What exactly happens when such a child is abandoned? While this contingency was provided for in previous drafts of the ART Bill (2020 ART Bill also simply prohibits it, without defining what happens in case the eventuality does occur), the current Bill does not address it. Will the procedure set forth in Sections 30, 32 and 38 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJA) then be activated so that the abandoned child is produced before the Child Welfare Committee and declared legally free for adoption? 33 Or given that the surrogate is a close relative of the intending parents, will there be further provisions for the extended family of the surrogate and the intending parents to adopt the child? Will intending parents or guardians also be penalized under Section 75 of the JJA which prohibits cruelty by biological parents or will they have an exemption like biological parents where this is due to circumstances beyond their control?

Restrictive eligibility criteria

Surrogacy is a novel mode of reproduction for individuals and couples, irrespective of their fertility conditions. To limit the ethical use of surrogacy to compelling circumstances or “medically indicated” cases, the law must lay down eligibility criteria for those who may be allowed to use it – delineating physiological (e.g. infertility or other medical conditions that may prevent a pregnancy) as well as social parameters (e.g. sexual orientation, marital status etc.). The Bill, however, lays down highly restrictive criteria. Section 2(p) defines infertility as “the inability to conceive after five years of unprotected coitus or other proven medical condition preventing a couple from conception.” This contradicts the definition of infertility in the 2020 ART Bill and also international standards, e.g. the World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as “a disease of the reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse.” 34 Conditions such as the absence of a uterus and other medical conditions that prevent carrying a pregnancy to term have not been covered by the Bill as exceptions.

Furthermore, Section 4(ii) delineates the purposes for which surrogacy can be undertaken. Section 4(ii)(e) includes “any other condition or disease as may be specified by regulations made by the Board.” This ground is vague and needs to be brought in line with Section 2(p) which defines “infertility” as including “any proven medical condition preventing a couple from conception.” 35 Intending couples are also required to be childless according to this Bill, with the exception of section 4(iii)(c)(III) which allows surrogacy if such couple has a “child and who is mentally or physically challenged”. This is highly problematic in its framing as it is tantamount to implying that having differently abled children is as good as having none at all, and should not find a place in any progressive legislation. 36

The Bill also permits surrogacy only for heterosexual couples who have been married for five years. As the law in India, as articulated by the courts, moves towards recognizing and deliberating upon other forms of coupledom such as cohabitation and “relationships in the nature of marriage”, 37 this Bill takes one step backwards. When it comes to the form of a couple’s relationship, the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 offers protection to women who may live or have lived in a shared household in a “relationship in the nature of marriage.” The Assisted Reproductive Technologies Bill, 2010 similarly defined the term “couple” to cover two persons living in India and having a sexual relationship that was legal in India, thus allowing them to commission surrogacy.

In terms of who can become a surrogate, Section 4 (iii) (b) (II) of the Bill allows only women who are “close relatives” of the intending parents to become surrogates. However, in a glaring gap, the Bill does not define the term “close relative”. To begin with, the requirement that the surrogate be a close relative drastically limits the number of women who can potentially carry the pregnancy for the intending couple. Since the close relative has to be between 25 and 35 years of age and be married with a child under section 4(iii) (b) (I), such a close relative is likely to be a sister (either a sibling or a first cousin), or the wife of either of their brothers, or their niece (through a sibling or cousin). Yet, given that infertility can result from several genetically transmitted medical conditions, the pool of close relatives will likely be further restricted to relatives from the family of the spouse who does not suffer from infertility. These restricted eligibility criteria will inevitably frustrate the surrogacy option for many couples, hence there is a need to revisit this requirement. 38

Importantly, the restricted eligibility criteria for intending parents and surrogates envisaged under the Bill are open to challenge on constitutional grounds, especially discrimination and violation of the right to privacy. Firstly, single men and women, cohabiting heterosexual couples and same-sex couples, who are not allowed to commission surrogacy under the Bill can challenge the Bill as discriminatory for violating their rights to equality and equal protection before the law under Article 14 of the Constitution. For any legislative classification to be reasonable under Article 14 of the Constitution, the classification must be founded on intelligible differentia and the differentia must have a rational nexus to the objective sought to be achieved by the legislation. 39 The Bill permits only heterosexual, married couples to commission surrogacy when infertile and thus form their families. It does not afford single men and women, heterosexual co-habiting couples and same-sex couples this option. These differentiae seem intelligible in an empirical sense but not a normative sense. On what basis can a heterosexual married couple be considered to be inherently capable of being a parent and forming a family whereas a single person or cohabiting couple or same-sex couple cannot do the same?

Further, the differentia have no rational nexus with the objective of the Bill which is to “constitute National Surrogacy Board, State Surrogacy Boards and appointment of appropriate authorities for regulation of the practice and process of surrogacy and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.” The Bill might seek to regulate surrogacy by limiting its availability to a narrow sliver of commissioning parents; however, this differentiation between who can be a commissioning parent and who cannot, has no rational nexus with regulating surrogacy. Restricting surrogacy to heterosexual married couples does not help regulate surrogacy better than if it were available to single men and women, cohabiting couples and same-sex couples. Moreover, single women are allowed to adopt under the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956. Single and divorced persons are allowed to adopt children as per Section 57 of the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015. 40 The 2005 ICMR guidelines also permitted a single woman to be an intending parent. 41 Finally, Section 3(e) of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019 requires that transgender persons not be discriminated against in terms of “access to, or provision or enjoyment or use of any goods, accommodation, service, facility, benefit, privilege or opportunity dedicated to the use of the general public or customarily available to the public.” Hence denial of surrogacy services to transgender persons will violate the 2019 Act.

In relation to same-sex couples, it is noteworthy that when the Ministry of External Affairs introduced a surrogacy visa in 2012 for foreign commissioning couples, gay couples were excluded on the basis that the constitutional status of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, which criminalized “sex against the order of nature” was unclear. 42 At that time, the Delhi High Court had read down Section 377 as being unconstitutional but that the decision was pending appeal before the Supreme Court. 43 However, the legal landscape has dramatically shifted since then. The criminalization of consensual sexual activity between adults of the same sex by Section 377 has now been held to be unconstitutional for violating Articles 14, 15, 19 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. 44 The transformative power of the Indian Constitution and the triumph of constitutional morality over social morality are being marshalled to campaign for equality for LGBT persons in all walks of life including in marriage and specifically for same-sex marriage. 45 The Supreme Court itself observed in Navtej Johar that the right to privacy included the right to union and companionship, with Justice Dhananjaya Chandrachud observing that:

The constitutional principles which have led to decriminalization must continuously engage in a rights discourse to ensure that same-sex relationships find true fulfillment in every facet of life. The law cannot discriminate against same-sex relationships. It must also take positive steps to achieve equal protection. 46

The Bill must therefore embrace the decision in Navtej Johar in letter and spirit by allowing same-sex couples to avail of surrogacy. Further, the Supreme Court has held that a law can be held to violate Article 14 when it is manifestly arbitrary. In Shayara Bano v Union of India, Justice Rohinton F. Nariman held that

Manifest arbitrariness, therefore, must be something done by the legislature capriciously, irrationally and/or without adequate determining principle. Also, when something is done which is excessive and disproportionate, such legislation would be manifestly arbitrary. We are, therefore, of the view that arbitrariness in the sense of manifest arbitrariness as pointed out by us above would apply to negate legislation as well under Article 14. 47

The Bill’s restrictions on who can commission surrogacy are likely to fall foul of Article 14 on this count of manifest arbitrariness as well.

Secondly, there have recently been significant shifts in the right to privacy jurisprudence under the Indian Constitution. Admittedly, there is no explicit right to reproduction protected under the Indian Constitution. However, in B.K. Parthasarthi v Government of Andhra Pradesh, 48 the Andhra Pradesh High Court upheld the “right of reproductive autonomy” of an individual as a facet of the “right to privacy” which is protected under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. This reading was recently reiterated by the Supreme Court in Puttaswamy v Union of India, where it held that “a woman’s freedom of choice whether to bear a child or abort her pregnancy are areas which fall in the realm of privacy” (Justice Chelamaswar, para. 38). 49 The majority also noted that:

‘the sanctity of marriage, the liberty of procreation, the choice of a family life and the dignity of being are matters which concern every individual irrespective of social strata or economic well-being. The pursuit of happiness is founded upon autonomy and dignity. Both are essential attributes of privacy, which makes no distinction between the birth marks of individuals’ (majority, para. 157). 50

The provisions of the Bill can therefore be challenged by single men and women, cohabiting heterosexual couples and same-sex couples for violating their reproductive autonomy, dignity and right to privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution. Needless to say, the state can place restrictions on the right to privacy to protect its legitimate interests but only if it meets the three point test set out by Justice Chandrachud in this decision, namely, that there be a law, second, that the law is reasonable rather than manifestly arbitrary and finally, that the means which are adopted by the legislature are proportional to the object and needs sought to be fulfilled by the law. Given the liberalizing nature of relationships and family forms in India today, a fact recognized by Indian courts from time to time, the state would be hard-pressed to argue that the purpose of the Bill, which is to regulate the practice and process of surrogacy can be better met by restricting surrogacy only to heterosexual married couples. The Bill restricts the reproductive autonomy of groups other than such married couples and this restriction is neither reasonable nor proportional to satisfying the law’s objectives. Commentators have thus observed that the Bill may have an uphill task meeting the just, fair and reasonable standard required for laws that restrict the right to privacy. 51

Admittedly, surrogacy is unique when compared to other cases of reproductive rights wherein women typically assert their right to privacy vis-à-vis the state. In the case of surrogacy, the rights of the intending parents to form a family sit alongside the reproductive autonomy of the surrogate to have a baby on her terms even if it is governed by a contractual arrangement with the intending parents. This relationship is likely to be a highly unequal one. In this context, the state’s insistence on altruistic surrogacy might appear to be a valid restriction on the reproductive autonomy of the surrogate in the interests of preventing commercialization from which third parties benefit at the expense of the surrogate. In reality however, requiring altruistic surrogacy in the absence of compensation to her for her reproductive labour and without corresponding protections for the surrogate under the Bill in fact amounts to an unreasonable and disproportionate encroachment on the surrogate’s reproductive autonomy. Thus it violates the surrogate’s right to privacy under Article 21 as the restriction is not just, fair and reasonable. As Dipika Jain and Payal Shah have argued, it is only by enhancing reproductive rights while paying attention to gender equality (by side-stepping gender stereotypes) 52 and to structural factors that undermine women’s access to health more generally that reproductive justice can be achieved. 53 Using gender stereotypes that naturalize women’s reproductive labour as divine ignores the structural inequalities that mediate a surrogate’s performance of such labour. The Bill reinforces these stereotypes while paying lip-service to addressing structural inequalities.

Beyond altruistic vs. commercial surrogacy: “compensated surrogacy” and the prevention of exploitation

Globally, there have been polarized debates on whether surrogacy should be altruistic or commercial. Notwithstanding this distinction, all surrogacy arrangements are ultimately contractual where the intending couple and the surrogate enter into an agreement. It is perplexing that in the Bill there is no mention of a contract between the intending couple and the surrogate mother. Section 6(1) specifies the need for written informed consent from the surrogate mother, but this is limited to medical procedures and side-effects. A more expansive contract or agreement is needed to govern the arrangement, clearly spelling out the rights and duties of each party, namely, the intending couple and surrogate mother, including but not limited to the medical procedures involved. Moreover, although Sections 2 (b) and (f) mention “surrogate mother or her dependents or her representative”, they do not specify who can represent her or under what conditions. For a Bill with a stated objective of preventing the exploitation of surrogate mothers, exclusion of the provision for a contract is a serious omission.

The Bill seeks to ban commercial surrogacy and opts for altruistic arrangements allowing only for payment of medical expenses and insurance coverage for the surrogate. 54 However, only reimbursing costs or expenses incurred is not sufficient in lieu of the time and effort that the surrogate devotes to the process. In fact, the PSC pointed out that “permitting women to provide reproductive labour for free to another person but preventing them from being paid for their reproductive labour is grossly unfair and arbitrary.” (para 5.18). It further noted that “the altruistic surrogacy model as proposed in the Bill is based more on moralistic assumptions than on any scientific criteria and all kinds of value judgments have been injected into it in a paternalistic manner.” (para 5.22)

Adopting a pragmatic and rights-based approach, the PSC recommended:

The Committee is of the view that medical expenses incurred on surrogate mother and the insurance coverage for the surrogate mother are not the only expenses incurred during the surrogacy pregnancy. For any woman who is going through surrogacy, there is a certain cost and certain loss of health involved. Not only will she be absent from her work, but will also be away from her husband and would not be able to look after her own children. The Committee, therefore, recommends that surrogate mother should be adequately and reasonably compensated. The quantum of compensation should be fixed keeping in mind the surrogacy procedures and other necessary expenses related to and arising out of surrogacy process. The compensation should be commensurate with the lost wages for the duration of pregnancy, medical screening and psychological counselling of surrogate; child care support or psychological counselling for surrogate mother’s own child/children, dietary supplements and medication, maternity clothing and post-delivery care. (para 5.24)

In contrast, the RSC concurred with the approach of the Bill. It observed:

Compensatory surrogacy gives rise to some of the teasing questions:- whether there could be or should be any compensation for the noble act of motherhood; how much compensation could be treated as condign (sic) for a woman who agrees to rent her womb; whether any standard price or cost for this noble act of motherhood could be fixed, whether renting out of her womb by a woman for some material consideration could be considered as an ethical practice and the woman would get the same respect as other women and mothers get in the society. The appropriate and judicious response to all these questions appears to be in the negative and it is in this background that the most acceptable option for surrogacy is the altruistic one … At the heart of the altruistic surrogacy lies the fact that it is bereft of any commercial consideration, it is a social and noble act of highest level. The surrogate mother … willfully and voluntarily resolves to do something worthwhile for the society and she, instead of being considered as getting involved in an immoral and unethical practice, sets an example of being a model woman in the society indulging in altruistic and selfless service as other normal mothers do … ” (para 4.9)

The RSC recommended that the Bill allow for the payment of additional expenditure to cover nutritional food and maternity clothing for the surrogate which are “vital for the well-being and upkeep” of the surrogate but did not itemize it unlike the PSC. Further, while the PSC recognizes the reproductive labour of the surrogate as such, the RSC bases its arguments on gendered stereotypes of “ideal” motherhood thus glorifying women’s labour but at the same time devaluing it. Even when the RSC refers to the PSC report on other matters, it differs on the question of compensation. In its deification of women as mothers, exalting surrogate mothers for their altruism by the very fact of agreeing to act as one, the RSC sets aside a vital argument that the PSC report had highlighted: the labour in surrogacy, notwithstanding the inherent nobility and altruism on the part of women who act as surrogates. An important extension of the argument by the PSC is that compensation for the work of surrogates is a better way of recognizing their contribution than mere exaltation. In any case, merely eliminating the provision for a fee or remuneration for the surrogate, does little to make surrogacy non-commercial, in a context where surrogacy is provisioned almost exclusively in the private healthcare sector by a multi-million dollar ART industry. Compensating the surrogate, whether she is an unrelated consenting woman, a “close relative” or a “willing woman” is only fair recognition of work, far from commercialization.

Finally, the Bill’s provisions on uncompensated surrogacy are likely to violate Article 23 of the Constitution. 55 In determining whether it indeed violates Article 23, the main question is whether giving birth to a child amounts to reproductive labour and whether engaging in this form of labour without any compensation (which the Bill requires) does not amount to begar or forced labour. Indian courts have in various contexts acknowledged that the act of bearing a child is reproductive labour. Pertinent here is a long line of cases on the status of the unpaid domestic and care work of housewives and how courts compensate dependents for such labour under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 when the housewife dies. In National Insurance Co. Ltd. v Minor Deepika 2009 56 which came up before the Madras High Court, Justice Prabha Sridevan remarked on how unpaid domestic and care work was the foundation of human experience and how it must be valued by the courts by providing compensation to the deceased housewife’s daughter (Paragraph 9). This line of reasoning was confirmed by the Supreme Court in 2010 in the case of Arun Kumar Agarwal 57 wherein the court noted the range of tasks that a housewife engages in, including the cooking of food, washing of clothes and teaching of small children. While the focus of the courts in these decisions was on unpaid care work, they also implicitly recognized the reproductive labour performed by mothers in bearing children, sometimes awarding compensation for the loss of a foetus. Moreover, in several cases which discussed surrogacy such as the Baby Manji case 58 and the Jan Balaz case, 59 contracts for commercial surrogacy were not held to be illegal thus offering implicit recognition of the reproductive labour of surrogates. Therefore, there are adequate grounds for considering the labour of bearing and giving birth to children as labour for purposes of Indian law.

We then need to ask whether provisions of the Bill which allow unremunerated surrogacy by a close relative of the intending couple (or for that matter of any “willing woman”, as the RSC recommended and the government has since accepted according to media accounts 60 ) would amount to begar or forced labour thus violating Article 23 of the Indian Constitution. Indian courts have held that “begar” requires showing “that the person has been forced to work against his will and without payment.” 61 The level of force required here is high such that it negates the will of the individual. To understand what is meant by force, consider PUDR v Union of India, 62 also referred to as the Asiad Games case, where Justice Bhagwati elaborated on the meaning of the term “force” under Article 23 of the Constitution and concluded that “any factor which deprives a person of a choice of alternatives and compels him to adopt one particular course of action may properly be regarded as ‘force’ and if labour or service is compelled as a result of such ‘force’, it would be ‘forced labour’.” 63 Since only a person suffering from hunger or starvation would accept a job where the remuneration is less than the minimum wage, the court reasoned that any labour remunerated at a level less than the minimum wage would be considered to be forced labour under Article 23. This interpretation of force has been reiterated by the Supreme Court in a long line of cases including under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005. Although the interpretation of force has been elucidated by the courts in relation to market forces which men are typically subject to, we could equally apply this structural understanding of force to coercion applied by family members in a patriarchal society such as India, where the rate of marriage for women is 94.8% 64 and families exert considerable power over their lives and reproductive decisions.

If close relatives of the intending couple, especially sisters-in-law or daughters-in-law are persuaded to reproduce not only for their nuclear family but also for the extended family in order to preserve their marital life, the levels of social pressure experienced by them can be of a similar nature to that exercised by the market on male labourers. Indeed, Section 39 of the Bill presumes such coercion. The proposed Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill 2018 (which was passed by the lower house of the Indian Parliament in July 2018 and lapsed before being introduced in the Rajya Sabha) also incorporates a specific offence of aggravated trafficking punishing any person who traffics a woman for the purpose of bearing a child by natural means or through the use of ARTs. 65 Irrespective of familial ties between the intending parents and the surrogate, it is exploitative to expect women to perform reproductive labour without being adequately compensated for it. Further, with no payment allowed for in the Bill, these women will be performing reproductive labour for less than the minimum wage attracting the application of Article 23 of the Constitution. 66 Admittedly, compensation is not an antidote to coercion but as the Supreme Court has noted, coercion is endemic, whether in the labour market or in marriage, and compensation can keep impermissible levels of exploitation at bay.

Criminalizing surrogacy

A heavily criticized aspect of the Bill is its excessive reliance on criminalization to prevent commercial surrogacy. Section 40 designates that “offences under this Act shall be cognizable, non-bailable and non-compoundable.” Section 35 of the Bill seeks to criminalize a range of processes and actors related to surrogacy, namely, doctors, owners of surrogacy clinics, other intermediaries or “any person” engaged in commercial surrogacy, advertising for it, sale of embryo or gametes for surrogacy, their import or conducting sex selection as part of surrogacy. Section 35(2) specifies a minimum mandatory punishment of ten years and with fine up to ten lakh rupees. Section 36 delineates punishments for medical practitioners and clinic owners, or persons employed by them for any contravention of the provisions of the Bill that are not addressed in section 35, namely, imprisonment for five years with fine of up to ten lakh rupees. Subsequent offences can potentially result in suspension of registration of the medical practitioner. Section 37 meanwhile punishes intending couples and other individuals initiating commercial surrogacy with a minimum mandatory imprisonment of five years and with fine which may extend to five lakh rupees for the first offence and higher punishments for subsequent offences. At the outset, these punishments are disproportionately high when compared to punishments in surrogacy laws around the world. 67 For example, in Israel and New Zealand, the highest punishment for violation of the surrogacy laws are no more than one year’s imprisonment.

The high level of criminalization under the Bill is consonant with the Indian state’s efforts over the past decade to don a paternalist mantle and introduce draconian laws against sexual violence, especially rape, child sex abuse and trafficking. These crimes are considered to be mala in se (wrong in itself) but the laws themselves have been ineffective at best, often generating unintended consequences and undermining women’s sexual autonomy and freedom of movement. 68 Well before this carceral turn, the Indian state has long legislated on mala prohibita (wrong because they are prohibited) offences. 69 These include offences under the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1986 where the activity of selling sexual services itself is not a crime but its commercialization through the involvement of third parties is. Surrogacy is another such activity where under the Bill, altruistic surrogacy is permitted but not its commercialization. There is however an extensive literature documenting how this schizophrenic approach to the sale of services produces considerable ambiguity in the minds of enforcement officials thus generating social stigma and high economic and penal costs borne by the most vulnerable actors in the industry, namely, the women themselves. 70

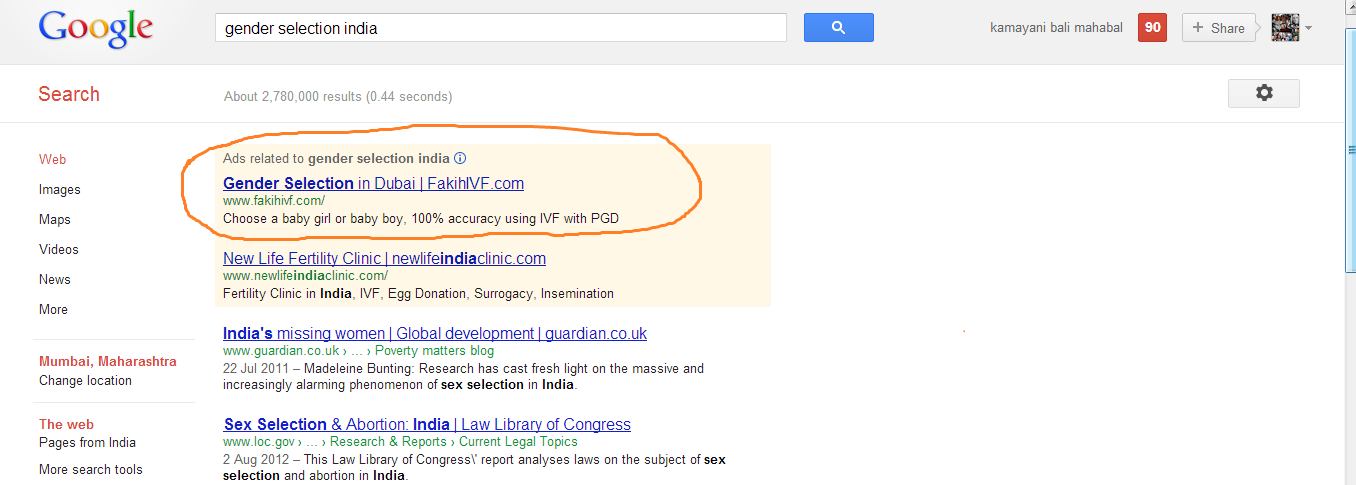

The unintended consequences of criminalization including their ability to create a push-down pop-up effect and the mushrooming of underground markets are well-documented and must be heeded before adopting a highly carceral approach to commercial surrogacy. 71 Consider Section 35(1)(a) which outlaws “individual brokers or intermediaries to arrange for surrogate mothers and for surrogacy procedures”. However, their individually-driven informal networks have spread across the country in the last decade, mostly through expansive word-of-mouth referrals with commission-based payments for every node of the network. 72 It would be challenging to completely dismantle them and gaps in implementation of this provision will result in the emergence of illicit black markets. In fact, soon after the first announcements about the prohibition of commercial surrogacy were made, there were reports of “surrogacy rackets” 73 being busted in major Indian cities in 2017. While “raids” and racket-busting may be seen as effective implementation, the spread of informal networks that have sustained the surrogacy industry for over a decade would be extremely challenging to reign in. Reproductive justice scholars have also long demonstrated how an overarching criminal regime which prohibits abortion through the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) with exceptions (in the form of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971) in fact leads to a chilling effect in women’s ability to access safe abortion on their terms thus undermining their bodily autonomy. 74 The medically mediated nature of the surrogacy sector means that criminalization will adversely affect women’s health. Experience from the implementation of the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994 shows that steep punishments and fines impede conviction and present a hurdle in the law’s implementation. 75

Furthermore, Section 39, a part of which reads as follows, presumes that all surrogates are forced into surrogacy thus denying that they are capable of exercising their choice in making decisions related to their bodies:

Notwithstanding anything contained in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, the court shall presume, unless the contrary is proved, that the women or surrogate mother was compelled by her husband, the intending couple or any other relative, as the case may be, to render surrogacy services, procedures or to donate gametes …

It could be that Section 39 is effectively a sub-clause of Section 37 (prohibiting the intending couple from seeking commercial surrogacy) where it reverses the burden of proof. Therefore, in cases where a prosecution is launched under Section 37, the intending couple would have to prove that the surrogate was not coerced; this would facilitate the conviction of intending couples. However, as it currently reads, it suggests that all surrogacy is presumed to be coerced, which frustrates the very purpose of the Bill. If the Bill does indeed presume coercion in every instance of surrogacy then it must amend section 4(iii)(b) to add an additional ground for issuance of the eligibility certificate which states that the appropriate authority must be satisfied that the surrogate mother was not compelled by the intending couple.

Finally, section 41 specifies that a court can take cognizance of any offence only when a complaint in writing is made by the appropriate authority or where a person or social organization has given 15 days’ notice to the appropriate authority of the alleged offence and intends to file a complaint. Given that this provision can be misused by competitor surrogacy clinics or NGOs acting without adequate information, and the timeframe within which the appropriate authority has to take action is short, more safeguards must be introduced in this section to prevent frivolous or malicious actions by private parties.

In conclusion: lessons for India from the global experience on regulating surrogacy

Over the last 40 years or so since the first IVF birth in 1978, many countries have regulated the use of ARTs including surrogacy. However, rarely has robust regulation of surrogacy come without a complementary regulation of the broader area of ARTs. In previous sections, we have demonstrated the pitfalls of attempting the regulation of ARTs and surrogacy in silos. We conclude this paper by drawing lessons from the experiences of other jurisdictions on surrogacy.

In a recent book offering an overview of surrogacy laws around the world, Jens Scherpe, Claire Fenton-Glynn and Terry Kaan 76 identify at least four approaches to surrogacy worldwide. These include: the prohibitionist approach where almost all aspects of surrogacy are prohibited including altruistic surrogacy. Countries in this category include France, Germany and Spain. Then, there are tolerationist countries like the UK and several provinces in Australia which allow for restricted forms of surrogacy such as altruistic surrogacy. With the limited availability of women willing to be surrogates however, couples in these countries have looked internationally to hire surrogates to complete their families. When they have returned, their governments have been forced to tolerate international surrogacy arrangements on pragmatic grounds to protect the “best interests of the child.” 77 Further, their courts had no possibility of investigating the commercial arrangements that their citizens may have entered into abroad. There are yet other countries that adopt a regulationist approach towards surrogacy by creating a mechanism for the state (often a High Court as in Greece and South Africa or an executive agency as in Israel, New Zealand and Portugal) to approve surrogacy before the transaction is initiated. Further, Greece allows for compensated surrogacy with an upper limit for remuneration and Israel allows for commercial surrogacy. Finally, there are liberal jurisdictions such as California and Russia which allow for commercial surrogacy to be regulated by contracts entered into by the parties without prior state approval.

India fell in the category of liberal countries in the initial years of the growth of the ART industry. Since 2016, when India started rethinking its liberal approach to surrogacy, there has been a reversal of trends internationally. Countries that once banned both altruistic and commercial surrogacy are having to deal with the adverse consequences of effectively “exporting” their surrogacy problem. They have therefore felt the need to adopt a more pragmatic approach to surrogacy at home. As India considers prohibiting commercial surrogacy and allowing the purest form of altruistic surrogacy (where no more than medical expenses and insurance costs for loss, damage, illness or death are borne by the intending couple), countries like the UK are considering a more permissive stance towards surrogacy. Hence, it is crucial for India to consider lessons from tolerationist and regulationist countries when passing laws on ART and surrogacy. Placing a high level of restrictions on surrogacy threatens to export the surrogacy market elsewhere. Given that the remaining liberal jurisdictions are costly venues for surrogacy, only the wealthiest Indians will be able to afford surrogacy, thus leading to a highly inequitable scenario regarding access to surrogacy in the country. Moreover, there remains the formidable risk of not being able to closely monitor such transactions abroad. Instead, we need to return to the National Guidelines for the Accreditation, Supervision and Regulation of ART Clinics in India, 2005 issued by the ICMR which had an entire chapter (Chapter 7) on providing ART to economically weaker sections of society, including through clinics in the public sector, by addressing the high cost of ovarian stimulation hormones and reducing dependence on multi-national corporations for these drugs.

Further, several tolerationist and regulationist countries like Israel and South Africa have robust written Constitutions (like India) where citizens have litigated the right to use surrogacy services as single parents, cohabitating couples in a permanent relationship and as same-sex couples. As outlined earlier, the Bill by excluding cohabiting couples, 78 single persons, and same-sex couples 79 from pursuing surrogacy violates their right to privacy and reproductive autonomy as set out in the 2017 Puttaswamy judgement of the Supreme Court. The Indian government must anticipate constitutional challenges on these fronts.

Against this backdrop, the recommendations of the RSC on the sheer unworkability of the Bill as passed by the Lok Sabha are very welcome. Yet, in recommending the liberalization of the eligibility criteria while retaining altruistic surrogacy, the RSC’s 2020 report has muddied the regulatory waters yet again. On the one hand, like the proponents of the Bill, the RSC believes that the epitome of Indian motherhood is to reproduce children for the market, with “divine warmth and affection,” irrespective of detriment to the well-being of one’s self and family, thus valorizing freely provided reproductive labour. On the other hand, the inclusion of the term “prescribed expenses” leaves the door half open for some form of compensation, especially since the arrangement is not restricted to “close relatives”. Where the Bill seems to frustrate the very possibility of surrogacy through stringent eligibility criteria for both the intending parents and the surrogate, with restricted payments (medical expenses and insurance coverage) and carried out only for the domestic market, the RSC expands the eligibility criteria and allows OCIs and PIOs to pursue surrogacy thereby opening up the market. But, it incredulously expects that surrogates in the hopes of being “role models” for society, will carry a child through term for strangers without any compensation even when wealthy OCIs and PIOs commission surrogacy. Who would such “willing women” be and how would the government prevent their forced labour and exploitation? Even if the Committee’s suggestions are accepted, expecting the performance of reproductive labour for third parties without payment will raise the presumption that such labour is forced for lack of payment and will therefore violate Article 23 of the Constitution.

In conclusion, the government now has the reports of two parliamentary committees wherein the collective wisdom of more than 50 MPs has demanded a fundamental overhaul of the Bill. Even as some of the recommendations of the RSC seem acceptable to the government, there are some glaring omissions which may well tie up the Bill in constitutional litigation for years, particularly around issues of discrimination, right to privacy and forced labour, rendering uncertain (once again) the legal landscape for those who harbour the hope of making families through surrogacy. For all these reasons, it is important that as the government updates the Bill, it gives due consideration to these issues of fundamental importance. Otherwise, it would miss an important opportunity for sensible law reform.

Notes

1 This is the labour involved in performing social reproduction which is defined by Hoskyns and Rai to be “biological reproduction; unpaid production in the home (both goods and services); social provisioning (… voluntary work directed at meeting needs in the community); the reproduction of culture and ideology; and the provision of sexual, emotional and affective services (such as are required to maintain family and intimate relationships)” C Hoskyns and S Rai, ‘Recasting the global political economy: Counting women’s unpaid work’ [2007] 12(3) New Political Economy 297–317, 300.

2 A Bailey, ‘Reconceiving Surrogacy: Toward a Reproductive Justice Account of Indian Surrogacy’ [2011] 26(4) Hypatia 715–741.

3 G Aravamudan, Baby makers: The story of Indian surrogacy (Harper Collins 2014).

4 S Dasgupta and S Das Dasgupta, ‘Business as Usual?: The Violence of Reproductive Trafficking in the Indian Context’ in S Dasgupta and S Das Dasgupta (eds), Globalization and Transnational Surrogacy in India: Outsourcing Life (Lexington Books 2014) 194.

5 J Agnihotri Gupta, ‘Reproductive Biocrossings: Indian Egg Donors and Surrogates in the Globalized Fertility Market’ [2012] 5(1) International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 25–51.

6 M Rao, ‘Why All Non-Altruistic Surrogacy Should Be Banned’ [2012] 47(21) Economic & Political Weekly 15–17.

7 K Sangari, Solid:Liquid: A (Trans)National Reproductive Formation (Tulika Books 2015) 87.

8 ibid 78.

9 ibid 113.

10 A Pande, Wombs in Labor: Transnational Commercial Surrogacy in India (Columbia University Press 2014) 6.

11 Pande (n 10); S Rudrappa, Discounted Life: The Price of Global Surrogacy in India (NYU Press 2015); D Deomampo, Transnational Reproduction: Race, Kinship, and Commercial Surrogacy in India (NYU Press 2016); K Vora, Life Support: Biocapital and the New History of Outsourced Labor (University of Minnesota Press 2015); A Majumdar, Transnational Commercial Surrogacy and the (Un)Making of Kin in India (Oxford University Press 2017).

12 Pande (n 10) 23.

13 Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, Orders No. 25022/74/2011-F.I dated 9 July 2012, 7 March 2013 and 22 September 2015.

14 Jayashree Wad v Union of India, W.P.(C) 95/2015

15 The Assisted Reproductive Technologies (Regulation) Bill, 2020. Bill No. 97 of 2020, As introduced in Lok Sabha. See: <https://www.prsindia.org/billtrack/assisted-reproductive-technology-regulation-bill-2020> accessed on 22 September 2020.

16 Prof. MV Rajeev Gowda spoke against the exclusion of “Single parents, living partners, divorcees, same sex couples and couples, where one of the partners is not Indian” in accessing surrogacy (19 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 17.00 to 18.00, p.1).

17 Kahkashan Parveen highlighted the need to reduce the time period to define infertility to one year as against five years (19 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 17.00 to 18.00, p.35). Vijaysai Reddy spoke about the need to take “into account other medical conditions such as women may conceive but may not be able to carry for the nine months during her pregnancy or may have multiple miscarriages. There are conditions such as hypertension, diabetes that affects the pregnancy. These other conditions have not been taken into consideration while making the definition for infertility.” (20 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 14.00 to 15.00, p.2).

18 Abir Ranjan Biswas (19 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 17.00 to 18.00, p.15).

19 Prof. MV Rajeev Gowda (19 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 16.00 to 17.00, p.32).

20 Dr. Amee Yajnik argued that the needs and the rights of the child should actually be put at the centre in drafting a Bill on this subject (20 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 14.00 to 15.00, p.22).

21 Prof. Ramgopal Yadav (19 November 2019 Uncorrected Rajya Sabha Debates – 17.00 to 18.00, p.25).

22 Select Committee, Rajya Sabha, Report on The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019, para 4.8, p.22.

23 Select Committee, Rajya Sabha, Report on The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019, para 4.11, p.23.

24 It reads “commercialisation of surrogacy services or procedures or its component services or component procedures including selling or buying of human embryo or trading in the sale or purchase of human embryo or gametes or selling or buying or trading the services of surrogate motherhood by way of giving payment, reward, benefit, fees, remuneration or monetary incentive in cash or kind.”

25 PM India, ‘Cabinet approves the Assisted Reproductive Technology Regulation Bill 2020ʹ (PM India, 19 February 2020) <https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/cabinet-approves-the-assisted-reproductive-technology-regulation-bill-2020/> accessed 1 August 2020.

26 See Prabha Kotiswaran, ‘Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill needs a thorough review’ Indian Express (9 October 2020).

27 It states, “no woman, other than an ever married woman having a child of her own and between the age of 25 to 35 years on the day of implantation, shall be a surrogate mother or help in surrogacy by donating her egg or oocyte or otherwise.”

28 It specifies, “no woman shall act as a surrogate mother by providing her own gametes.”

29 For example, Canada and Australia require that at least one of the intending parents have a genetic link to the child born out of surrogacy. With transnational surrogacy, they often require proof of such link in the form of DNA test results. See, K Lozanski, ‘Transnational surrogacy: Canada’s contradictions’ [2015] 124 Social Science & Medicine 383–390 and Australian High Commission in New Delhi, ‘Children born through Surrogacy Arrangements applying for Australian Citizenship by Descent ‘ (Australian High Commission New Delhi India, Bhutan) <https://india.embassy.gov.au/ndli/vm_surrogacy.html> accessed 28 July 2020.

30 The RSC recommends that there be a genetic link between the child and the intending mother or intending couple. p. 26.

31 228th Law Commission of India Report, Need for Legislation to Regulate Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinics as well as Rights and Obligations of Parties to a Surrogacy (2009)<http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report228.pdf> accessed 1 August 2020.

32 K O’Donovan, ‘A Right To Know One’s Parentage?’ [1988] 2(1) International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 27–45; KS, Rotabi, and others, ‘Regulating Commercial Global Surrogacy: The Best Interests of the Child’ [2017] 2 J Hum Rights Soc Work 64–73.

33 If this is the case, the definition of “abandoned child” under Section 2 of the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015 must be amended to include not just biological or adoptive parents or guardians but also intending parents or guardians.

34 See the clinical definition of infertility by the WHO at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions/en/. Further, Section 2 (g) stipulates that couple “means the legally married Indian man and woman above the age of 21 years and 18 years respectively”. This needs to be read along with Section 2 (r) which defines “intending couple” as a couple who have been medically certified to be an infertile couple and who intend to become parents through surrogacy and Section 4(iii)(c)(I) wherein the age of the intending couple is between 23 to 50 years in case of female and between 26 to 55 years in case of male on the day of certification.

35 Interestingly, the RSC recommended the deletion of Section 2(p) of the Bill which defined infertility as the inability to conceive after 5 years of unprotected coitus, and did away with the need for medical certification of infertility. Medical indication for gestational surrogacy was sufficient and this has to be certified under Section 4(iii)(A)(I), para 4.20–21, p. 25.

36 The debates on disability and rights of the disabled include discussions on the critical importance of recognizing their personhood, strongly rooted in principles of human rights. See, E De Schauwer and others, ‘Desiring and critiquing humanity/ability/personhood: disrupting the ability/disability binary’ [2020] Disability & Society [Online], 16 March; P. Mittler, ‘UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Implementing a Paradigm Shift.’ [2015] 12 (2) Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 79–89. Moreover, such a provision in the Bill is in direct contravention of The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 that guarantees equality and non-discrimination for the disabled including a right to “life with dignity and respect for his or her integrity equally with others” in section 3(1).

37 D.Velusamy v D.Patchaiammal [2010], CA2028-2029(SC).

38 Possibly heeding the impracticability of these suggestions, the RSC has recommended the removal of this restriction. Any willing woman meeting the age criteria of the Bill can become a surrogate under Section 4(iii)(b); para 4.53, p. 31.

39 The State Of West Bengal v Anwar Ali Sarkar 1952 AIR 75.

40 Arijeet Ghosh and Nitika Khaitan, ‘A Womb of One’s Own: Privacy and Reproductive Rights’ [2017] 52(42–43), Economic & Political Weekly (EPW Engage), [Online] <https://www.epw.in/engage/article/womb-ones-own-privacy-and-reproductive-rights>, accessed 9 September 2020.

41 Unfortunately, here the Select Committee favoured only widowed and divorced women between the ages of 35 and 45 as eligible to pursue surrogacy provided they obtained a certificate from the National Surrogacy Board upon application. A couple of Indian origin also have to obtain a certificate from the National Surrogacy Board; para 4.24, p. 25.

42 Section 377 read as follows: 377. Unnatural offences – Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with 1[imprisonment for life], or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine. Explanation – Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section.

43 Naz Foundation v Government of NCT Delhi, 2009 S.C.C. OnLine Del 1762; the decision on appeal was rendered in Suresh Kumar Koushal v Naz Foundation, (2014) 1 S.C.C. 1.

44 Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India (2018) 10 S.C.C. 1.

45 See Oxford Union Address by Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju, [Online] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Lp6H4YYN-k accessed 9 September 2020

46 Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India (2018) 10 S.C.C. 1, 185.

47 Shayara Bano v Union of India (2017) 9 SCC 1, 262.

48 B.K. Parthasarthi v Government of Andhra Pradesh [2000] 1 ALD 199.

49 Puttaswamy v Union of India [2017] Writ Petition Civ 494/12,(SC) (hereafter ‘Puttaswamy’).

50 In another case Javed v State of Haryana (AIR 2003 SC 3057) however, dealing with electoral laws that bar individuals with more than two children from contesting elections to local bodies (panchayats), the Supreme Court upheld this restriction on the right to reproduce on the basis that it was justified for ‘socio- economic welfare and health care of the masses’ and ‘consistent with the national population policy’. This judgement was however rendered prior to the Puttaswamy decision; the Supreme Court’s judgement in Puttaswamy would be binding in future cases relating to autonomy in matters of reproduction.

51 Arijeet Ghosh and Nitika Khaitan, ‘A Womb of One’s Own: Privacy and Reproductive Rights’ [2017] 52(42–43) Economic & Political Weekly (EPW Engage), [Online] <https://www.epw.in/engage/article/womb-ones-own-privacy-and-reproductive-rights> accessed 9 September 2020. Also, Aparna Chandra argues that the Bill limits surrogacy not based on scientific data, but on conceptions of “public morality”-such as age criteria, number of pre-existing children of the commissioning parents and marital status of the parties. See, Aparna Chandra, ‘Privacy and Women’s Rights’ [2017] 52(51) Economic & Political Weekly, 46–50.

52 Surrogacy does defy gender stereotypes to the extent that it decouples birthing from the responsibilities of social motherhood.

53 D Jain and P Shah, ‘Reimagining Reproductive Rights Jurisprudence in India: Reflections on the Recent Decisions on Privacy And Gender Equality From the Supreme Court Of India’ [2020] 39(2) Columbia Journal of Gender And Law 1–53, p. 6.

54 Sections 2(b) and 2(f) of the Bill which define altruistic and commercial surrogacy mention this along with a prohibition of remuneration of any kind. However, these sections are ambiguous as to whether the surrogate mother is to be reimbursed for the medical costs or if the intending couple will take care of all the costs directly.

55 Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour (1) Traffic in human beings and begar and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited and any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law. (2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from imposing compulsory service for public purpose, and in imposing such service the State shall not make any discrimination on grounds only of religion, race, caste or class or any of them.

56 MANU/TN [2009] 1304.

57 Arun Kumar Agarwal v National Insurance Company [2010] 9 SCC 218

58 Baby Manji Yamada v Union of India (UOI) and Anr AIR [2009] SC 84.

59 Union of India & Anr v Jan Balaz and others [2009] SLA Civ 31639 (SC); Union of India & Anr v Jan Balaz and others [2010] CA 8714 SC.

60 HT Correspondent, ‘Rajya Sabha panel recommendations get Cabinet nod’ The Hindustan Times (Delhi, 27 February 2020) [Online] https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/rajya-sabha-panel-recommendations-get-cabinet-nod/story-itB4FkNggJq0qnNfoCY6FM.html

61 Ram Khelwan Pathak v State of U.P., [1998] 2 AWC 1171.

62 People’s Union for Democratic Rights v Union of India, AIR [1982] SC 1473.

63 ibid, para 5.10.

64 G Raveendran, The Indian Labour Market: A Gender Perspective Discussion Paper for Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016 (UN Women 2016) 11.

65 The draft provision s. 5 reads as follows:‘5. Trafficking for the purpose of bearing child. – Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force, whoever commits the offence of trafficking of a person for the purpose of bearing child either naturally or through assisted reproductive techniques for commercial purposes, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than ten years, but which may extend to life imprisonment and shall also be liable to fine which shall not be less than one lakh rupees.’ Available at https://www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/bill_files/The%20Trafficking%20of%20Persons%20%28Prevention%2C%20Protection%20and%20Rehabilitation%29%20Bill%2C%202018.pdf The base offence for this aggravated offence of trafficking lies in Section 370 of the Indian Penal Code where a person is trafficked by coercive means (including the use of threats, the use of force, or any other form of coercion, abduction, the use of fraud, or deception, or the abuse of power, or inducement, including the giving or receiving of payments or benefits, in order to achieve the consent of any person having control over the person recruited) for purposes of exploitation (“any act of physical exploitation or any form of sexual exploitation, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude, or the forced removal of organs.”). The fact that the Trafficking Bill visualizes women who are trafficked by market intermediaries for producing a child must alert us to the fact that similar levels of coercion can be exerted by the family as well, resulting in the exploitation of women.

66 In fact, a constitutional expert Gautam Bhatia has made a similar argument to characterize the unpaid labour of women as forced labour under Art. 23. See Bhatia, The Transformative Constitution A Radical Biography in Nine Acts (HarperCollins India 2019) 210–211.

67 Unfortunately, the RSC in its zeal to curb commercial surrogacy suggests that Section 38 be expanded to cover omissions to pursue altruistic surrogacy (p. 61) which if accepted would introduce considerable ambiguity in the law while also violating general principles for imposition of criminal liability.

68 Prabha Kotiswaran, The Carceral Politics of Sexual Violence: Notes on a Political Economy of Criminal Law, Second Annual Project 39A Lecture, National Law University Delhi, 2019; Preeti Pratishruti Dash, ‘Rape adjudication in India in the aftermath of Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2013: findings from trial courts of Delhi, [2020] 4(2) Indian Law Review, 244-266; Partners for Law in Development, Why Girls Run Away To Marry – Adolescent Realities And Socio Legal Responses In India, 2019, available at https://www.academia.edu/40718265/WHY_GIRLS_RUN_AWAY_TO_MARRY_ADOLESCENT_REALITIES_AND_SOCIO-LEGAL_RESPONSES_IN_INDIA; Raided: How Anti-Trafficking Strategies Increase Sex Workers’ Vulnerability to Exploitative Practices, SANGRAM. Available online at http://sangram.org/resources/RAIDED-E-Book.pdf

69 This distinction has long been debated by philosophers and scholars of criminal law; whether an offence is mala in se or mala prohibita often turns on whether the act is intrinsically morally wrong. This distinction is not the focus of the research at hand, but we find compelling philosopher Susan Dimock’s argument where she draws on social contract theory to define mala in se offences as offences involving “conduct that must be prohibited in any society united for mutual benefit on terms that are fair to all.” Mala prohibita offences on the other hand are “those wrongs that offend against rights and duties assumed by participants within valuable social practices, when participants are tempted to violate the rights of others or to neglect their own duties and doing so would undermine the practice or deprive it of its value.” Thus, insider trading is a mala prohibita offence that a society may (rather than must) choose to criminalize. S Dimock, ’The Malum prohibitum-Malum in se Distinction and the Wrongfulness Constraint on Criminalization’ [2016] 55(2) Dialogue 1–24, see pp 15, 21. Selling sexual services for money or bearing a baby for a couple in exchange for money are in our view similar examples.